Modernization

Learn more about government’s intention to modernize the museum to protect our historic holdings and provide better access to our collections.

“Repatriation is an act of reconciliation,” says the Royal BC Museum’s resident Repatriation Specialist, Michelle Washington.

Born and raised in the Tla’amin First Nation near the town of present-day Powell River, Michelle, whose ancestral name is Siemthlut, is quick to point out the ties between her day-to-day work and the important ongoing reflection and dedication towards change happening throughout British Columbia around truth and reconciliation, now officially recognized annually on September 30.

“Repatriation has been going on for a number of years here, but it is now backed by legislation and has become important for institutions under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA), and other overarching policies,” she says. “UNDRIP makes it really clear that the right to culture, identity, health, education, and spirituality is a very important human right to First Nations people here in BC and Indigenous people around the world.”

Michelle started at Royal BC Museum in the early 1990s doing data entry for the Birds of BC book in a room she describes as being “somewhere behind the mammoth’s butt.” Ironically, she reconnected with the museum while working for her nation to facilitate the return of ancestral remains and cultural objects. The Tla’amin Nation was one of the first in BC to repatriate items from the museum under the terms of their treaty.

She came back as a member of the First Peoples’ Cultural Council to manage content for the Our Living Languages exhibition in 2014 for a year before spending time with the museum’s Learning team where she helped provide educational opportunities for the public to learn more about First Nation languages and cultures. After years of community governance experience, she went back to university to finish her anthropology degree before ultimately returning to the museum to serve in her current Repatriation Specialist role.

Collections care and community partnerships are at the heart of her work, and those collections are no joke. The Indigenous Collections and Repatriation (ICAR) department safeguards some 15,000 cultural objects, 65,000 photos, 37,000 audio/visual items, 200,000 archaeological objects and records, and more than 350,000 historic documents, and the Indigenous Collections team is tasked with reuniting those objects with their home nations whenever possible.

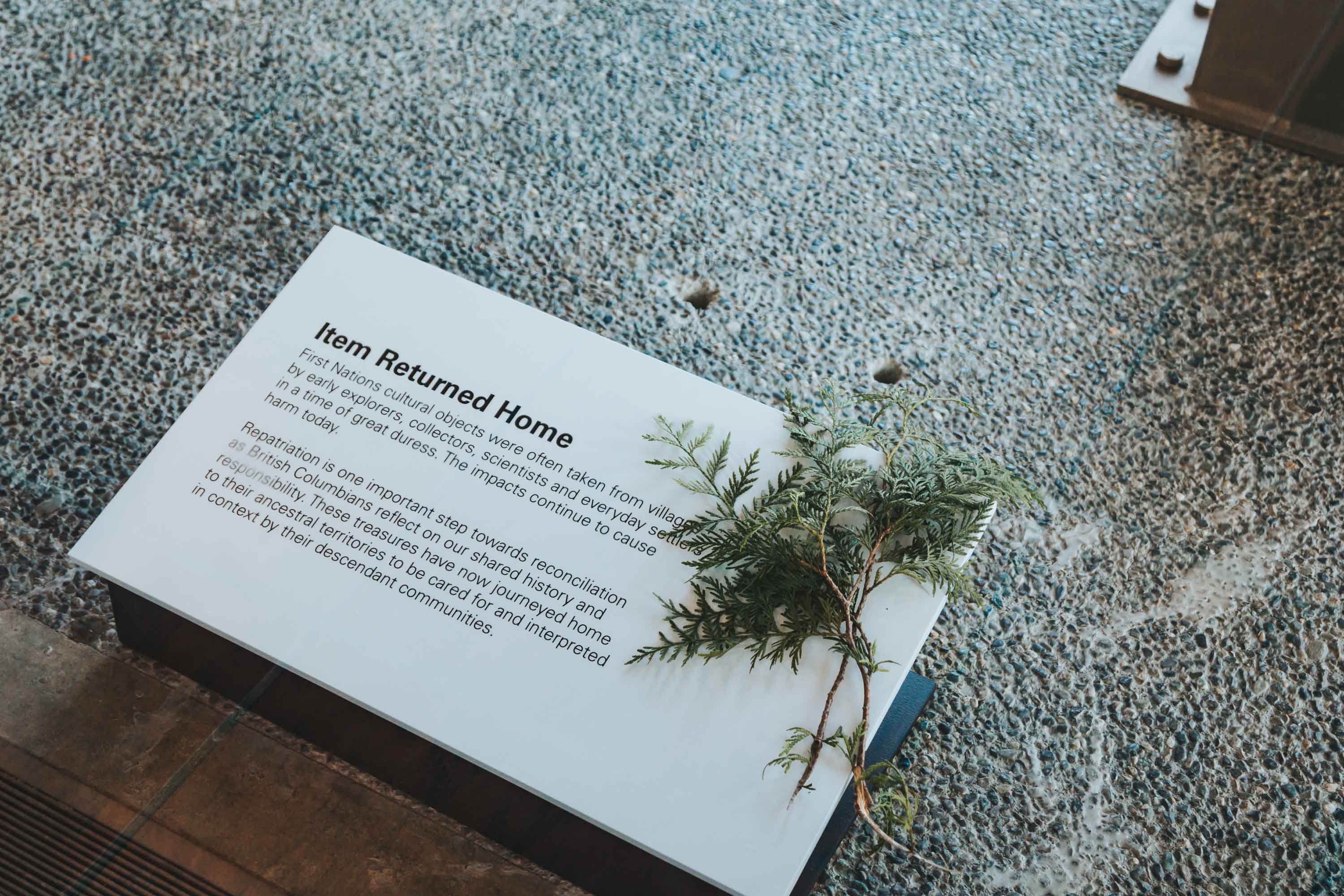

More than just a moral obligation, Michelle says museums now have a legal obligation to return Indigenous items of cultural and/or spiritual significance.

“Giving back things that have ended up here improperly is not just a way to right wrongs, but to heal the collections that are here,” she says. “So often you hear talk around reconciliation, but not really taking any action on it. This is one of the ways that a large institution like a museum can actually take action and put their money where their mouth is. To respectfully fix the unethical past practices that have done so much damage and are no longer legal.”

Beyond the ceremony and sacred ancestral connection nations have to their cultural belongings, repatriation has a widespread real-world impact on the nations who receive these treasures.

“Repatriation is connected to so many important initiatives in a community, like the revitalization of languages and updating traditional laws; it is an act of bringing back traditional forms of government through ceremony. It’s revitalizing art because artists can look at the works in context and learn how to recreate them through the stories they’re connected to. To see them in ceremony, intergenerationally in their own territory, and understand how some things like tools would have been made and used for specific environmental and culture-based hunting, gathering, and fishing practices their ancestors had,” Michelle says.

BC is in the top five percentile of culture and language diversity in the world and hold more than 60% of the Indigenous languages in Canada. Some 34 different languages, not including the various dialects, are spoken throughout the province. This immense diversity isn’t without its difficulties, however. In practice, Michelle says the return of belongings is led by the repatriating nation and it’s the museum’s responsibility to understand how to respectfully and appropriately approach these cultural exchanges beyond the formal legal and logistical requirements.

“One of the practices we have adopted is that when people come to repatriate their ancestral belongings, those ceremonies that happen here are now under their diverse laws, practices, and spirituality,” Michelle says. “Those special treasures they’re coming here to get were made by their ancestors long before settlers arrived and when their own people come to take them home, the ancestors recognize those practices and the language being spoken, and there’s a protection that happens so that work is done in a good way that their ancestors would have approved of. Not mine, not yours, not anybody else’s but theirs. That’s a really important part of how we’re changing the way things are done and how we are making things right.”

That mindset extends beyond the initial act of repatriation and into the preservation of those artifacts once they go home. Many organic items that were brought to the museum pre-1970, including wood and textiles, were sprayed with chemicals like arsenic or mercury. Those harmful chemicals still exist on those items to this day, and as a result, many ceremonial masks and regalia are no longer safe to be used in ceremony or handled without protective gloves.

Michelle says the museum is responsible for doing its due diligence in terms of identifying any risk factors such as conservation reports, display safety, insurance appraisals, proper provenance research, transport logistical issues, and other considerations that vary from one community to the next.

Beyond that responsibility, Michelle says it’s not up to institutions like museums to restrict cultural or spiritual practices. “UNDRIP is very clear now — it’s not up to any colonial organization to tell people how to live their lives anymore, so when we give things back, we don’t say ‘but you’re not allowed to do this or do that,’” she says. “The importance of preservation isn’t lost on First Nations people, but it’s also not up to organizations to dictate that anymore. Most nations build infrastructure, insure their belongings, and take the same care that anyone would with our heirlooms to keep them accessible for future generations. We call them artifacts here, but what they really are is treasured heirlooms that have been left. That’s how they’re treated when they go home, with reverence.”

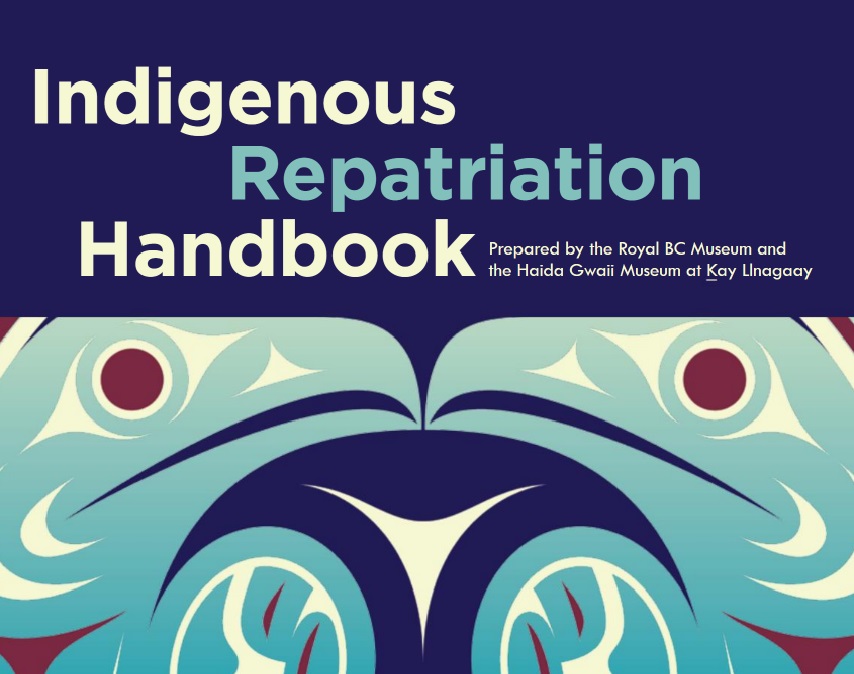

Michelle is currently updating the museum’s Indigenous Repatriation Handbook, a 162-page roadmap created to help guide nations and institutions on best practices for respectful and effective repatriations. The book, printed in 2019, has since been adopted around the world and is largely considered the gold standard when it comes to repatriation.

“It came out at the same time that the legislation was created so repatriation could become a lot more fulsome and a lot more meaningful and not just about institutions dictating what could go home, when it could go home, or how it could go home,” Michelle says. “We used to dictate a lot of the details around it and there was a huge power imbalance when First Nations came to the table. That playing field is now being leveled because of legislation like UNDRIP, TRC, and DRIPA."

For more information on the important work Michelle and the ICAR team do and to learn more about what the Royal BC Museum is doing to further truth and reconciliation for British Columbians, check out the links below: