Modernization

Learn more about government’s intention to modernize the museum to protect our historic holdings and provide better access to our collections.

It’s not every day that you hear a PhD-holding art curator extol the virtues of a social media platform, and yet, here we are, holed up in the Royal BC Museum’s on-site café discussing how 100,000 years of art history can be boiled down to the microcosm that is Instagram.

India Rael Young, the museum’s curator of Art and Images since late 2019, was kind enough to sit down with A Day in the Life of… to discuss her long road to the museum, the unexpected behind-the-scenes reality of interning at one of the world’s most renowned medieval museums, and all about her passion project for bringing forgotten histories back to life.

India Rael Young: I grew up in small-town Alaska and I spent a lot of time in our local state museum, which was actually modelled on the Royal BC Museum and Archives. Then I went away to college in New York for literature, but I spent all of my time off in the museums and art galleries. In my last semester, I got an internship at the Cloisters, which is a medieval museum that’s part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was at that internship where I realized you could work at a museum as a full-time thing—that’s a whole job. Then I set about getting a job in a museum.

IRY: It was legendary! It was a funny place, as museums are, but I do remember that they had a little lunch room in the middle of the building—teeny tiny—and only a giant antique table would fit in there, so you’d have to tuck around it. I was sitting next to the most important curators in the world for medieval art and they’d be chatting about their weekends and I’d be overhearing their conversations about why they weren’t going to the baseball game. It really made me feel like these are my people [laughing], this is where I want to spend my time. But then there’s also a real magic to being behind the scenes in museums. At the Cloisters, they had a lot of their collections installed and displayed in their library and in their offices, so they were really special spaces.

IRY: Just an appreciator. Just a quality appreciator. I have a life goal of retiring to a little beach in Peru called Paracas, and becoming a potter, making some ceramics. But you know, it’s more of a hobby goal than a professional goal.

IRY: Someone in my masters or PhD program shared with me that if you want to work in the fields of academia or museums, you have to think of it like being in the army. You just go where the job is. That said, I’ve been living between Victoria and elsewhere since 2007. This was the place I expatriated myself after Bush won the election for the second time.

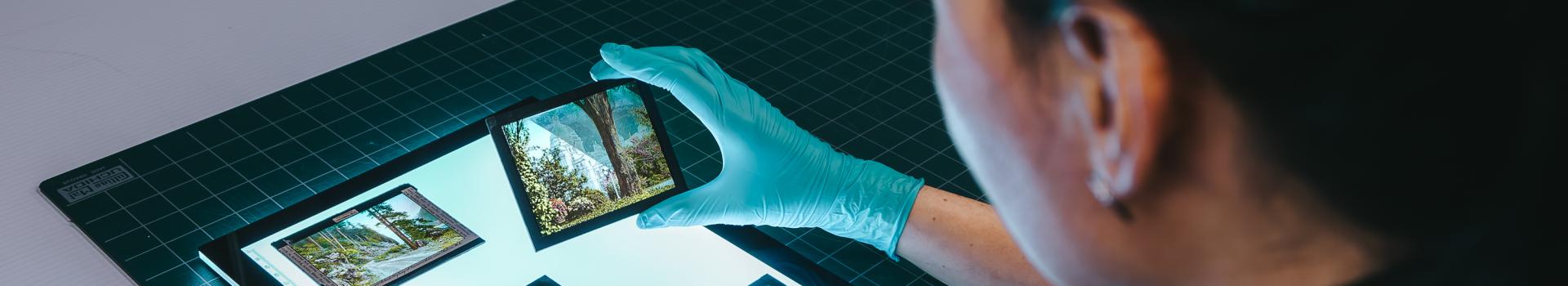

IRY: Because Instagram. One of the wonderful things that Instagram has revealed to us in recent years is that humans think visually and share culture and knowledge through visual images, and both art and photography are the historical means of doing that. What’s been really exciting about working in the collections here is getting to know many little-known artists and sharing their histories with the world. Some of the research I did when I first got here was about women artists in BC. Reaching out to women artists in the collection and people who remember them has been really rewarding. It’s rewarding to develop the histories and biographies of works and artists in the collections, many of which have been under-researched and exhibited.

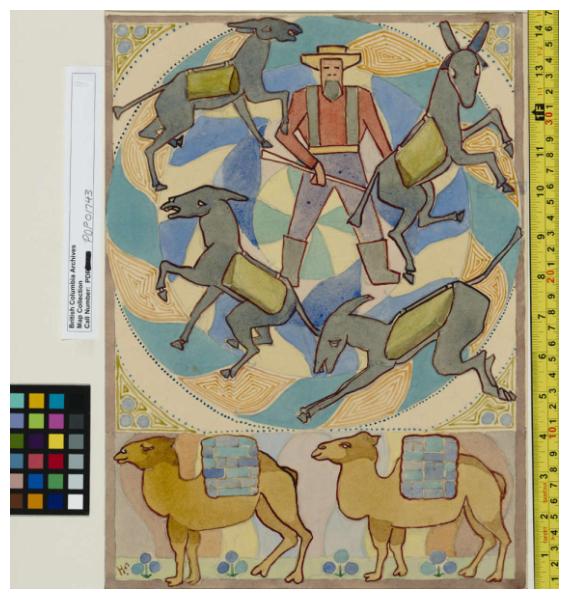

IRY: Hilda Vincent Foster. When I arrived at the museum, we had 21 pieces of hers and had never exhibited her works. We didn’t have a biography for her; I don’t even think we had her life dates written down. Through researching, I’ve been able to write in a clear history of Victoria in the mid-century by figuring out who she was and who her community was. It was a history we already had at the archives, we just didn’t have an ability to tell it.

IRY: The main avenues a curator has to share their research and knowledge is through exhibitions and through writing research papers or teaching. A project that I’m working on with Andrea Walsh and Jennifer Robinson at UVic is an exhibition that’s going to be hosted in Port Alberni next year around the works of George Clutesi. The museum has about 10 works by Clutesi that we’ll get to include in the exhibition. We’re working with the Clutesi family and members of Nuu-chah-nulth Nations. It’s going to be pretty beautiful.

IRY: It’s the dream! It’s really the dream. It’s only possible because of our team’s long-term relationships that we’ve slowly been cultivating and growing over decades. For instance, in working with Hilda Vincent Foster, some of the research meant looking through the records and newspapers, but the main way I learned about Foster and how and why she created her works was by connecting with the people who knew her and building those relationships.

IRY: The main differentiation is that we’re the government archive. We’re able to trace the way the government was interested in supporting the arts during some administrations and not supporting the arts during other administrations. We have the ability to tell those political stories, which is quite interesting. We also have what, in the industry are called vernacular photographs, which are photographs that aren’t fine art photography. Essentially every other photograph: your snapshots, your family photos and your government photos. The BC Archives has about five million predominantly vernacular photographs. They really help us tell, in a very Instagram kind of way, the visual and cultural stories of British Columbia. We can see so much in an image that we don’t need to explain.

IRY: The BC Archives opened in 1894 and it was the main place to tell the histories of British Columbians. The earlier archivists were both voracious and thoughtful in what they collected, and that has built this amazing collection of photographs from all across the province, from all kinds of folks, telling all kinds of stories that are social, political and environmental.

Learning Programs that showcase India's work:

This week in History:

Learning Portal Pathways related to India's collection:

***Some responses have been edited for length and/or clarity***