Modernization

Learn more about government’s intention to modernize the museum to protect our historic holdings and provide better access to our collections.

Today marks the launch of our newest book, Deep and Sheltered Waters—author David R. Gray’s vivid social history of a fascinating Vancouver Island community and place: Tod Inlet, near Victoria, BC.

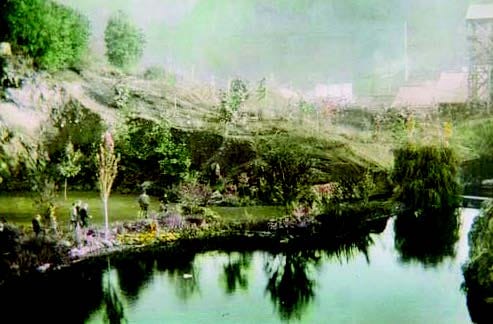

Many people now associate Tod Inlet with the world-famous Butchart Gardens, which overlook the waterway. But Gray starts the story further back, grounding the book in the narrative of the inlet’s original inhabitants: the Tsartlip First Nation, for whom the area is known as SNIDȻEȽ, Place of the Blue Grouse.

Gray then introduces readers to more recent denizens of the inlet, including the community of immigrant workers from China and India, and the other company workers at Robert Pim Butchart’s cement plant. The natural world is as much a presence as people in the book, which chronicles how the land around the inlet was ultimately developed into public parkland and the Butchart Gardens.

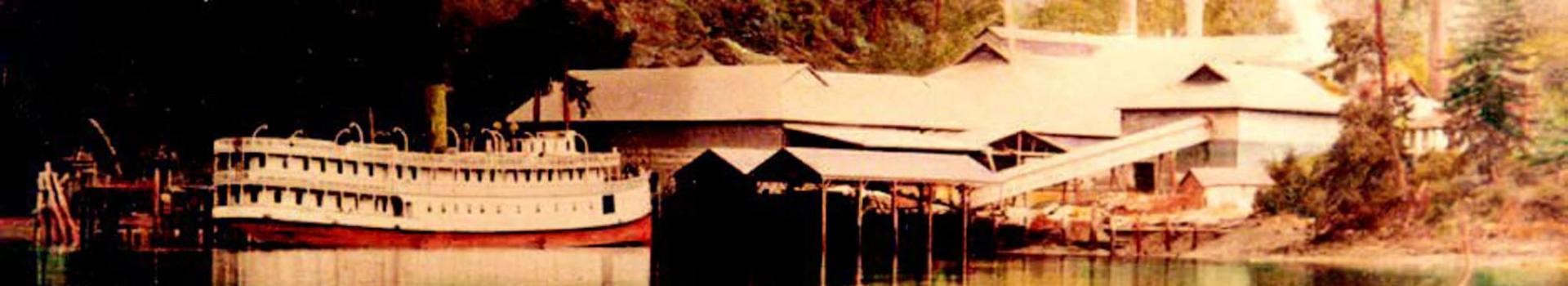

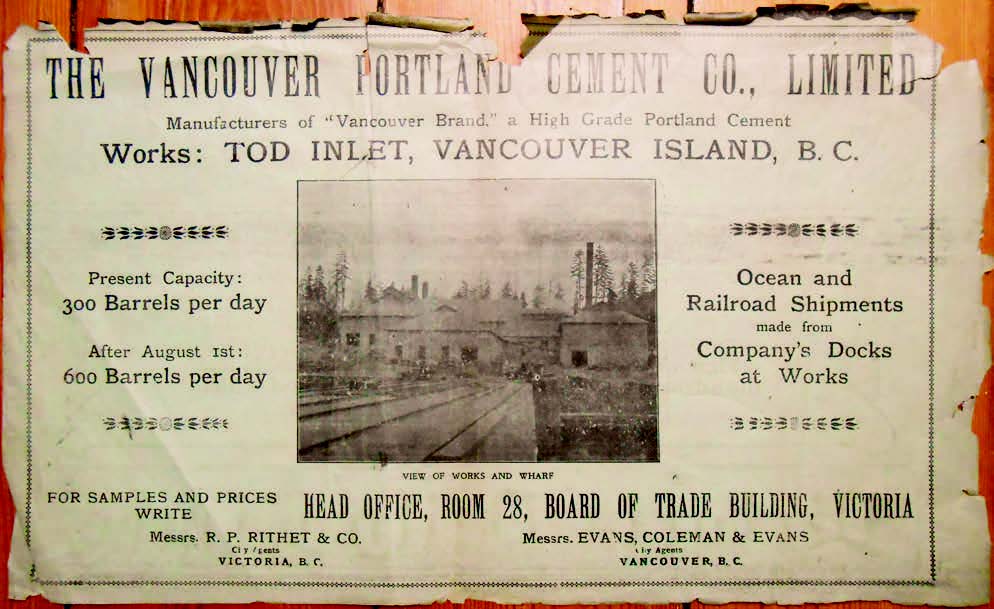

The cement plant, run by Butchart’s Vancouver Portland Cement Company, was the first large, successful cement plant in BC. Butchart’s company bought acreage for the plant in 1903 and construction began in June 1904. But now, more than a century later, hardly any vestige of this enormous industrial complex remains.

The story reflects the distinct but interwoven communities at Tod Inlet and includes original eyewitness accounts—recorded nowhere else—from people the author interviewed about their experiences. The following excerpt highlights the tough conditions for some workers at the Tod Inlet cement plant (which is central to the story of the community) and the resilience of the people living with them.

The Sikhs at Tod Inlet had a separate kitchen and bunkhouse from the Chinese workers. In 1907 the Sikh bunkhouse was described as “a small one-storey bunk house, some seventy feet by forty.”

Jeet Dheensaw, son of Hardit Singh, who arrived in 1906, remembered his mother’s stories of the Sikhs living in shacks with dirt floors, using cardboard for insulation and flour sacks as blankets. Material possessions were virtually non-existent. There were few houses, and the men slept four or five in one room. She said the men had no raincoats at first, and they got used to working in the rain, as they did not want to spend their wages on new clothing. They preferred to use “old stuff” left behind by others over spending money on new things.

Jeet remembers, “My dad and my uncle, that group of people, used to just have shacks there, working and staying in shacks, making their own food and living on dirt floors. In winter it got bitter, so they used to put planks down, but that’s all. They survived. When something fell down, they just added up another board or something and stuffed newspapers, whatever they could get their hands on, if nothing else mud even, just to keep the elements away. There was nothing, no beds, no tables and chairs.”

One man was assigned to do the communal cooking for the Sikh community, and each worker gave one day’s wages to the cook each month. One of the men who prepared the food in exchange for money was named Katar. Katar Singh was a blood relative of Hardit and Gurdit Singh, known as “Uncle” to Jeet Dheensaw and remembered as very strong. The Sikhs at Tod Inlet apparently followed the tradition of using two cooking fires side by side: one for cooking lentils and vegetables, the other for cooking chapati (flatbread) on a steel plate griddle. Norman Parsell and the other young boys living at Tod Inlet often watched the Sikhs cooking their chapati on an iron plate over an outdoor fire and were often invited to join the meal.

Lorna Pugh (née Thomson) told me a story of her father, Lorne Thomson, and Claude Butler Sr., hunting up in the Partridge Hills above the inlet in about 1910 and being caught by the darkness. They decided to stay the night up there rather than run the risk of going over one of the cliffs in the dark. When they came down at dawn the next day, they came out of the woods opposite the Sikh village: “After crossing Tod Creek they approached the [Sikh] campsite, where the [Sikh] employees of the cement company lived. The cook offered them tea, for which they were very grateful. The water was heated in a large brick trough, and the cook dipped his finger . . . into the trough to test the temperature of the water before giving them their tea. . . . It was hot and helped them to continue on their way home.”

Excerpted from Deep and Sheltered Waters: The History of Tod Inlet, by David R. Gray; $29.95 (paperback) and $11.99 (ebook). Available through local bookshops, the Royal Museum Shop and online at rbcm.ca/todinlet; use code todinlet to receive 20% off through Nov. 20, 2020.