Modernization

Learn more about government’s intention to modernize the museum to protect our historic holdings and provide better access to our collections.

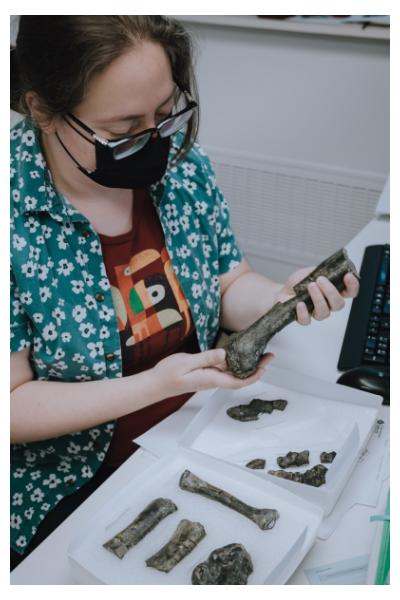

With the rest of the Palaeontology team playing dinosaur bone Tetris in the collection stacks behind us (space is a hot commodity for the growing collection), Dr. Victoria Arbour, Curator of Palaeontology and freshly back from nearly two weeks in the Sustut Basin finding new dinosaurs to add to the museum collection, sat down with A Day in the Life of… to talk dinos, digs, and a little BC-born fella by the name of Buster.

Victoria, who holds a PhD and Masters in Biological Sciences from the University of Alberta, has been with the Royal BC Museum since September 2018 and bears the distinction of naming the first unique dinosaur species ever found in British Columbia. But more on that a little later…

Victoria Arbour: Because dinosaurs are cool. It’s not a really interesting story, I was just one of those kids that liked dinosaurs and never really grew out of that phase. Now I get to do it all day, which is pretty awesome.

VA: [laughing] I’m partial to ones that I’ve named, but it feels a bit gauche to say that. I like armoured dinosaurs with tail clubs. They’re called ankylosaurs. They’re like huge prickly coffee tables.

VA: No. I count myself pretty lucky that I get to do this. There are well under 1,000 of us. Probably closer to 500 dinosaur-specific palaeontologists around the world. But palaeontology is more than just dinosaurs… anything that was ever alive can become a fossil and there’s someone who studies that. There are people that work on fossil plants or fossil insects or fossil algae.

VA: One of the things that’s fun about being in BC as a dinosaur person is that a lot of people don’t realize we have dinosaurs here, and that’s partly because they’re not that easy to find. But we do have them and what we do find will probably be different than what’s been found in other places. We just don’t have the Badlands that Alberta has where you can just walk around [and find bones] — you have to go in a helicopter or go on a jetboat and it becomes a lot harder and more expensive to do here.

VA: You have to have rocks that are the right age and the right type to have a fossil in them. Dinosaurs didn’t live all throughout time; they lived in a particular chunk of time, just like we live in a particular chunk of time. So, you have to have rocks that are at that right chunk time, at the surface, somewhere you can get to them, and not formed, say, a kilometer underground in lava. The main issue in BC is that a lot of our rocks got smooshed and folded into the mountains so you can’t find fossils in them anymore. Lots of BC basically just has the wrong aged rocks exposed at the surface, so they’re either too young or too old, or they were deposited in the ocean or somewhere where you’re not really going to find dinosaurs.

VA: You look at geological maps. Other geologists have gone out and mapped the rocks and done age dating. That being said, you can go to a place with the right age and date of rocks and still not find dinosaur fossils for random reasons. You also often do it based on where someone has already found a fossil. In one case, a geologist had found dinosaur bones in northern BC, so I was like “let’s go back and keep looking there.” I call that specimen “Buster”.

VA: There was a geologist, Kenny Larson, working in BC in 1971 who found some bones and held onto them. He moved to Nova Scotia, where I’m from, and donated them to Dalhousie University while I was an undergrad there. Then my professor was like, “Victoria, these are weird bones. Why don’t you work on these for your honours thesis?” They ended up being some of the first dinosaur bones ever found in BC. Then 15 years later when I knew more things, I was able to identify them as a unique species for British Columbia and it’s BC’s first unique named dinosaur, which is pretty fun.

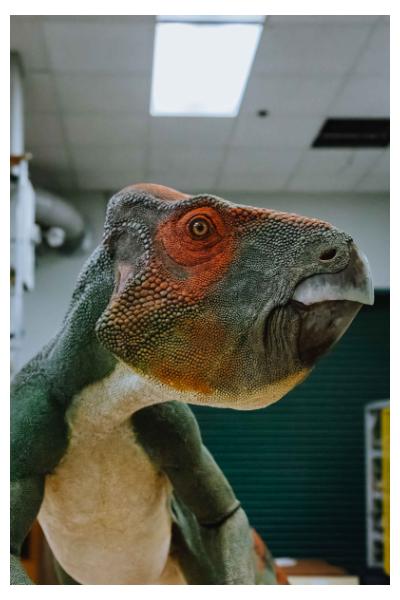

VA: It’s not a very “household name” kind of dinosaur. It’s a group called Leptoceratopsidae. It’s basically a smaller hornless relative of the Triceratops, and the full name for Buster is Ferrisaurus sustutensis, which basically means “The Iron Lizard from the Sustut River” which is where he was found.

VA: Realistically, an average day is a lot like what other people do. I answer emails, I go to meetings, I help keep the collection organized and stuff like that. The field work is like this really cool, important, concentrated part of my job for only a couple weeks at a time, a few times a year. It’s very cool, but it’s definitely not the whole time on the job. When we go out in the field, one of the places I go is very remote in the mountains, so we get dropped off by a helicopter and eat dehydrated meals and treat our water.

VA: There’s so many different questions you can ask and get answers to with fossils. Fossils are the record of how life has changed on Earth over time, like records of extinction and why extinction happened. Fossils help you understand how life reacts and evolves in response to climate change or rising sea levels. The fossils are the key data for that, and you can’t answer those questions without fossils to look at. It also just tells you interesting things about what animals were like in the past and how they adapt to different things. With my guys [ankylosaurs], I’ve spent a lot of time looking at why they have tail clubs and how they use them.

VA: I actually really like Jurassic Park. It’s dated now because it came out in 1993, but the first movie was a pretty cutting-edge scientific representation of dinosaurs. It was talking about the connection with living birds and showing them as active animals with complex behaviours. That was showing them not as monsters, but as real animals. A lot of it holds up. People have debunked certain things, but if you look at the whole vibe, I still really like it as a film and how it talks about science.

***Some responses have been edited for length and/or clarity***

Want to learn more about Buster and some of the other palaeontology work happening at the Royal BC Museum? Discover more below.

RBCM@Outside